1. The Dual Structure of the Balance Sheet: Stock and Flow

In general accounting, the balance sheet (BS) is often described as a “stock” statement, capturing the financial position of an entity at a specific point in time. In contrast, the profit and loss statement (PL) is a “flow” statement, reflecting the changes in revenue and expenses over a certain period.

However, the BS and PL are not entirely separate. Items on the PL inevitably impact the BS, and some BS accounts essentially represent flows. For example, retained earnings reflect the cumulative net income from past PL statements, while accounts receivable may increase as a result of revenue recognized in the PL but not yet collected in cash.

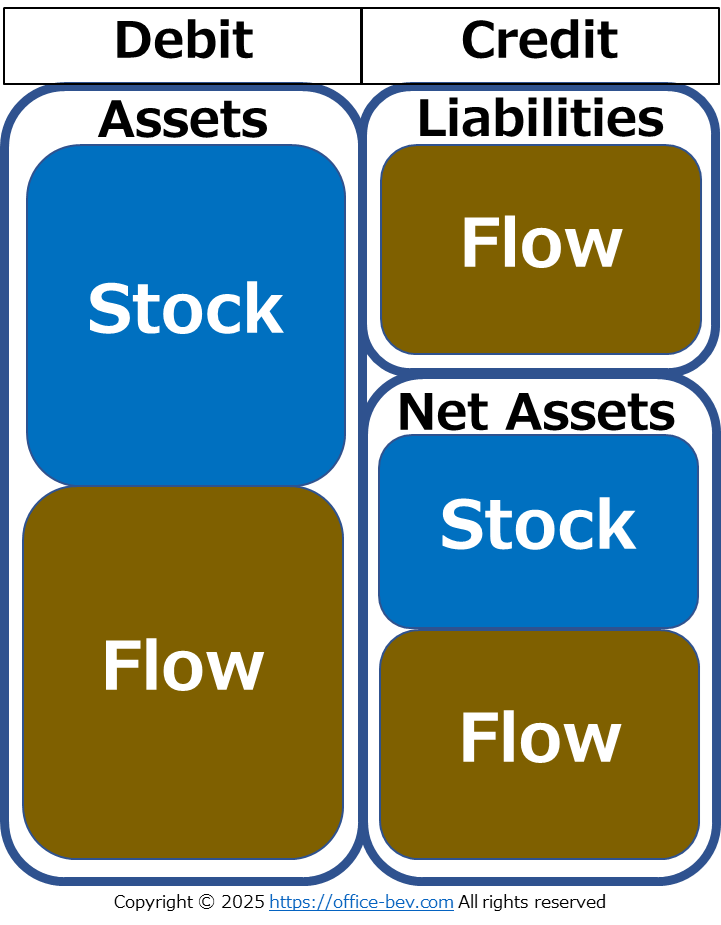

In this light, the BS, while appearing static, contains dynamic elements derived from past or anticipated flows. Conceptually, the balance sheet can be divided into two broad categories:

- Stock-based items: Assets with already realized value—such as cash or physical property.

- Flow-based items: Assets or obligations arising from past or expected future transactions, often dependent on counterparty action.

This distinction sets the stage for a deeper structural interpretation of the BS.

2. The Structure of Flow: Claims and Obligations as Relational Constructs

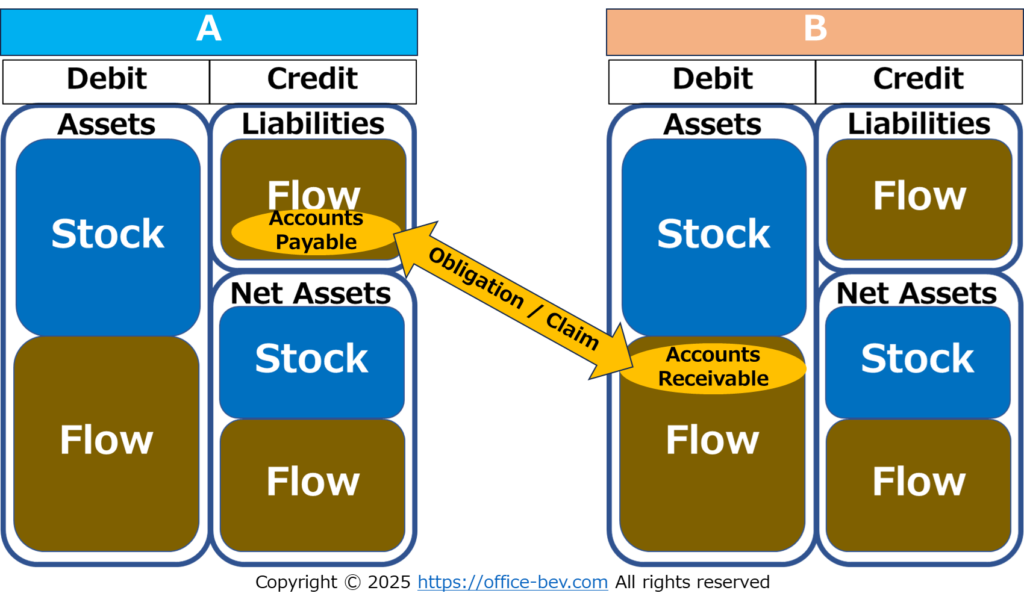

When we examine the flow-based elements within the BS, we find they are not self-contained. Rather, they rely on relationships with other parties—structured as claims and obligations.

For example, accounts receivable represents a claim to receive payment from a customer, which is only meaningful if the customer fulfills their obligation to pay. This relational pairing is fundamental to many BS items: payables, prepayments, accrued expenses, and so forth. They all presuppose an external counterparty whose future action is critical to value realization.

In short, many flow-based components in the BS are not simply accounting constructs—they are relational constructs, embedded in legal, institutional, and social expectations.

3. Trust as the Foundation of Claims and Obligations—In Other Words, Fiction

These relational constructs—claims and obligations—do not stand on their own. They are grounded in a more fundamental assumption: mutual trust.

Take accounts receivable again. It only functions as an asset because there is a shared belief that the customer will, in the future, pay what is owed. This belief is not a physical reality—it is a socially constructed expectation. Yet, this expectation is powerful enough to influence financial statements, corporate valuations, and even capital markets.

This leads us to the core insight: such structures are a kind of fiction. Not fiction as falsehood, but fiction as collective belief—a system sustained by shared trust and reinforced through institutions, contracts, and norms. This type of fiction forms the very foundation of modern finance and accounting.

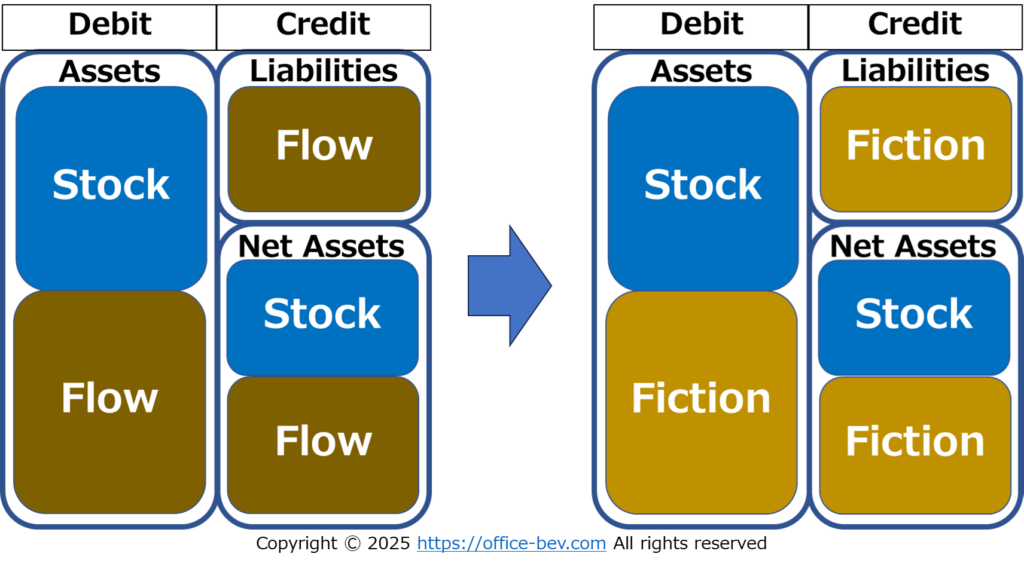

4. The Balance Sheet as a Dual Structure: Fiction and Stock

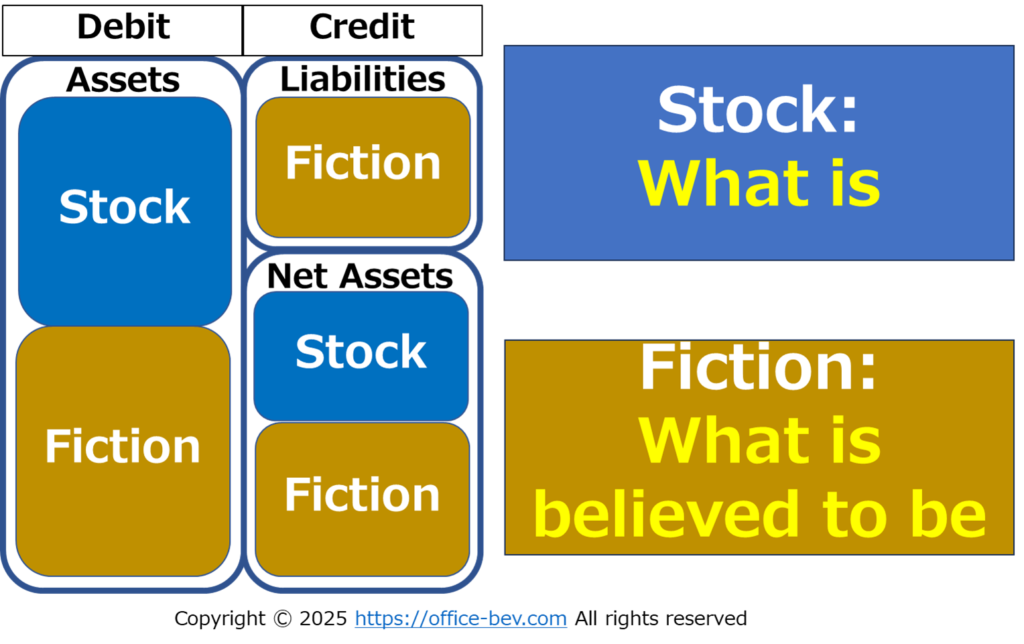

From this perspective, we can now reframe the BS not simply as a combination of stock and flow, but more abstractly as a dual structure composed of:

- Stock: Realized, tangible, or settled assets—those that do not depend on counterparties (e.g., cash, inventory, property).

- Fiction: Conditional, relational, or expected values—those that rely on social trust and future fulfillment (e.g., receivables, prepayments, obligations).

The BS presents a formal symmetry between assets and liabilities, but behind that symmetry lies an asymmetry in ontological status—some values are realized, while others are merely believed.

In this light, the BS is not merely a record of “what is,” but a representation of what is believed to be real—a structure made of both substance and shared imagination.

5. Applying the Framework: Fiction and Stock Across the Balance Sheet

Let us now apply this framework to the actual components of the balance sheet—assets, liabilities, and equity:

(1) Assets (Left Side of BS)

Assets contain both stock and fiction:

- Stock: Cash, land, goods in inventory—already realized value.

- Fiction: Receivables, prepayments, loans—value contingent on future action by counterparties.

(2) Liabilities (Right Side of BS – External Sources)

Liabilities are fundamentally relational:

- They represent obligations to others (repayment, delivery, etc.).

- Their existence depends on the counterparty. Therefore, liabilities are entirely fictional in structure, grounded in trust and enforceability.

(3) Equity (Right Side of BS – Internal Sources)

Equity seems like pure accumulation, but contains both elements:

- Stock: Retained earnings, paid-in capital—values that have already materialized.

- Fiction: For example, in-kind capital contributions (e.g., shares in another company) depend on external entities. Additionally, third-party investors may expect returns or governance rights, creating quasi-obligations toward shareholders.

→ Equity thus combines fiction and stock, blending internal accumulation with relational expectations.

6. Conclusion

The balance sheet is more than a static record of assets and liabilities. It is a dual structure: a synthesis of realized stock and fictional value grounded in social trust. By interpreting the BS in terms of what is and what is believed, we uncover the deeper foundations of modern financial systems—where fiction, far from being deceptive, becomes the engine of coordination, investment, and collective imagination.

1 thought on “The Dual Structure of the Balance Sheet: Fiction and Stock”

Comments are closed.